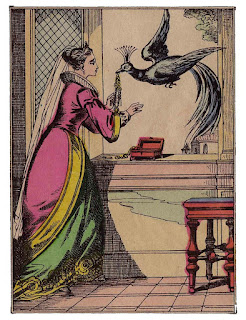

In one of Madame d'Aulnoy's classic fairy stories, “The Blue Bird” an abused princess survives incredible trials and transformations. Disguised as a beggar girl, she at last manages to gain access to the Echo Chamber in the castle of King Charming, who loves her as she loves him but believes her lost. What is said in the Echo Chamber can be heard distinctly in the royal bedchamber above. The princess wails her story of love and loss, assuming it will awaken the king to the fact that she is alive and available and recall him to the pledges they exchanged.

But night after night, the king fails to hear. The princess has used up nearly all of the magic a good witch gave her — which has enabled her to buy entry to the Echo Chamber — before she learns that the king does not hear her because he takes a sleeping-draught every night. She manages to bribe a page to withhold the sleeping potion. Awake in the night, the king hears her love pleas, goes in search of her, and they are united.

This is a much more relevant story for our times than the theme of the sleeping princess. Here the woman has to wake up the man, as is so more often the case. How many “sleeping kings” do we know? How many forms do their “sleeping draughts” take? Whenever you run into a guy who has lost touch with his dreams, who may even say, “I don't dream”, remember you may be dealing with a sleeping king, and you may be called on to play the role of the awakener.

The

very adult message in this story made me want to know more about the author.

Where did her clarity of perception, amongst all the fantasy and finery (and

raw horror, too) come from? The story of the author of “The Blue Bird” is

fascinating, and takes us into the primal depth of lived experience from which the

pre-Disney and pre-Victorian fairytales come — in this case, not from peasant

folklore but from the no less brutal life dramas of France's real-life

princesses.

At age fifteen, Marie-Catherine le Jumel de Barneville was kidnapped from a convent school and raped under the pretext of an arranged marriage — the polite name for an arrangement by which her father sold her to a rich and depraved aristocrat three times her age. The Baron d'Aulnoy was odious, a heavy drinker and gambler with very unpleasant sexual penchants.

Three years into the marriage, it looked like Marie-Catherine had found a way out of her cage when her husband was arrested on charges of high treason against the king. However, under torture two of the accusers confessed that they had invented the treason charges because they were Marie-Catherine's secret lovers. The baroness had to flee to Spain, where she restored herself to royal favor — over many years — by functioning as a secret agent for the French.

We derive the term “fairytale” from this extraordinary survivor,

Marie-Catherine d'Aulnoy.. She titled her first collection, published in

1697, Les Contes des Fées. She spun her tales for adults, rather than

children, in her seventeenth-century salon, in fashionable colloquial style, as

reflected in the subtitle of her second collection, Les Fées à la

Mode. Hers is a true-life story of spinning soiled hay into gold.

Text adapted from Active Dreaming by Robert Moss. Published by New World Library.

2 comments:

This is fascinating. I had never heard about this aspect of fairy tales before.

I love this story. It re-affirms for me that the old tales are deeps rivers of wisdom and a safe-haven for the Sacred Feminine. This story also resonated with two recent synchroicities about loss of hearing and mentions of a future Big Pharma(Active Dreaming) with a recent article about opioids and memory loss. Thank you!

Post a Comment