Monday, September 28, 2015

Temple of Toyen

When I first looked in your waters

I saw only blind larvae,

spongy belugas and unlovely phalluses.

A flash of green lightning made me look again.

Your Temple of Night opened to me.

I fell through its meaty door in space

and saw you mixing your colors

with blood, semen and ichor.

You give us the dream history

of the world at night.

I rush from canvas to canvas

hungry for more and more.

I follow you through all the tides

of sleep and dreaming and red-eyed insomnia,

the rise and fall of palaces and madhouses

from the amniotic ocean of night.

I fell into your vision in a white house

in a green park with a sycamore that knows me

and a shelter for wandering poets

where the sign is a merry command. Versify.

- Prague, September 25, 2015

Art by Toyen: top, "Temple of the Night" (1954); bottom, "Sleeping" (1937).

Labels:

Czech Surrealists,

Kampa Museum,

Kampa Park,

Prague,

Robert Moss poems,

Toyen

The mossy side of the ash

The pillars of the ruined cathedral

reach for the sky

like the masts of a shipwreck.

This earth has drunk blood and fire

over all the generations

when it was a highway of war.

The ash remembers.

Its double trunk

suggests a woman open for love

or a mother holding her baby.

I choose the mossy side

and enter her embrace.

This is a place where

I can always come

to see with Bohemian eyes

and cherish soul

that awakened in me here

among stone and ash.

- .Panenský Týnec, Bohemia, September 24, 2015

-

Labels:

ash tree,

Bohemia,

Panenský Týnec,

Robert Moss poems

Thursday, September 24, 2015

In the House of Madonnas

National Gallery in Prague, at the Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia

In the collection of medieval Old Masters of Bohemia in the National Gallery, I did not expect to be excited by rows and rows of paintings of the most familiar scenes from the Christian story. Then I woke up to how the artists, confined to a limited list of approved subjects by the theology of the time and what their ecclesiastical and noble patrons were willing to pay for, gave flight to their imagination and human experience within the frames of the expected conventional scenes.

So here's a Jesus with a goldfinch in his hand. And here are any number of Madonnas, to suit all tastes in men and all the shades of belief and desire. Some are great queens in finery, crowned or double crowned. Some (especially those carved from wood) look like they have just come from the kitchen or from sewing, or from a romp in a hayloft or a meadow full of mushrooms and wildflowers. The Madonnas are blonde and dark-skinned, homely and breath-stoppingly lovely, willowy and buxom.

I start to imagine the artists with their models, with a wife or mistress or mother, or that peasant girl who is entering the fields of love and art for the first time, when the harvest is golden over the land. The theme of the Madonna as mistress in these images from the late 14th century is nowhere as shockingly explicit as in France a century later, when Jean Fouquet painted Agnès Sorel, King Charles VII's favorite mistress, as madonna lactans.

I feel a wave of empathy as I see how human love charges divine love in the Bohemian collection, and how the creative imagination of great and original artists dances through the fences of prescribed forms. And I remember that the Goddess takes many forms.

Photos by RM

Wednesday, September 23, 2015

Tracks of Ceridwen and Celtic heroes in Prague

Prague

There are four ways to enact and embody a mythic story, one of the kind that may be missing from history but are always going on. The first way is that of the Minstrel, the second is that of the King.

Photo: "Stone sculpture of Celtic hero" by CeStu

There are four ways to enact and embody a mythic story, one of the kind that may be missing from history but are always going on. The first way is that of the Minstrel, the second is that of the King.

The Minstrel roves and rambles, using

humor and nudge-nudge suggestion to get some laughs and disguise the cutting edges

of the tale. He reads aloud from a text couched in antique language that is

hard for modern listeners to understand. The text seems to be an early

translation from the Mabinogion or a similar Welsh source. It speaks of Ceridwen,

whose name is spoken here as Ceri-dew. There are lines like, “Ceridew did hie

after him with her besom”.

I am eager for the King’s version, though this one will be darker. I do not recall the last two ways of engaging with the myth, but surely a Priestess will take charge at some point. And perhaps we will even hear from a poetic Mage.

I am eager for the King’s version, though this one will be darker. I do not recall the last two ways of engaging with the myth, but surely a Priestess will take charge at some point. And perhaps we will even hear from a poetic Mage.

Feelings: intrigued by this fresh invitation to dream archaeology.

Reality: It’s not really strange to dream into

Celtic traditions on my first night back in Prague. There were large Celtic

settlements – known as oppidums – in and around Prague in ancient times. The

Celts came to Bohemia in the fifth century BC and a Celtic tribe, the Boli,

gave Bohemia its name. There is a stone sculpture of a Celtic warrior head from Msecke Zehrovice, near Prague, in

the Národní Muzeum,

together with many other Celtic finds.

One of the great shapeshifting stories from world mythology is the Welsh tale of Ceridwen’s pursuit of Gwion, the boy who swallowed the magic drops from a potion she was brewing in her cauldron of inspiration and intended for another. The wrathful witch-goddess hunts him as a hound chases a hare, as an otter goes after a fish, as a hawk pursues a bird in the air. At last the goddess swallows Gwion as a hen gobbles a seed of corn. Rebirthed as a beautiful radiant boy, he survives to become Taliesin, “Radiant Brow”, the inspired Poet-Mage.

One of the great shapeshifting stories from world mythology is the Welsh tale of Ceridwen’s pursuit of Gwion, the boy who swallowed the magic drops from a potion she was brewing in her cauldron of inspiration and intended for another. The wrathful witch-goddess hunts him as a hound chases a hare, as an otter goes after a fish, as a hawk pursues a bird in the air. At last the goddess swallows Gwion as a hen gobbles a seed of corn. Rebirthed as a beautiful radiant boy, he survives to become Taliesin, “Radiant Brow”, the inspired Poet-Mage.

Photo: "Stone sculpture of Celtic hero" by CeStu

Tuesday, September 22, 2015

The howler on the plane

en route to Prague

I have a whole chapter in my new book Sidewalk Oracles on my adventures and misadventures during my airline travels around the world. They are evidence that my survival strategy as a very frequent flyer often works: if your plans get screwed up, look for a new opportunity or at least a fresh story. Real writers know that if nothing goes wrong you don't have much of a story. However, as I embarked on nearly 20 hours of straight travel from my home to Prague on Monday, I decided I could do without a new story on this trip. I announced as much to the airline gods: "I don't need a new story today."

They heard me, up to a point. All my flights arrived on time, or early, connections were easy, and my bag came to meet me as I walked to the carousal at Vaclav Havel airport. On the longest flight, from Dulles to Vienna, the only empty seat on the plane was the one next to mine. So I got extra legroom and sprawl space, but no interesting conversation with a stranger. There was the small matter of the baby three rows ahead of me. This was the loudest howling baby in human history. Every time it started up, it felt like an air raid siren had gone off just above my head. This happened every fifteen minutes, without preamble, for the whole 8-hour flight. Goodbye to any chance of sleep or proper rest on that redeye flight, though I had boarded sleep-deprived afetr staying up reading most of the previous night. However, the howler in the night brought me an unlikely gift. As I was ripped again and again out of drifty liminal states, I found that I had strong imagery and compelling ideas for a possible new book I had never considered before, though if I bring it off it will marry many of my life themes, dream adventures and experiences of walking on the mythic edge. I can't say more until the writer in me has had a chance to work on this. Writers write. I have never been inclined to say too much about what may be in the works until the work is done. But I'll share my one liner from the trip: A howler can monkey with you to a purpose.

Drawing by RM.

I have a whole chapter in my new book Sidewalk Oracles on my adventures and misadventures during my airline travels around the world. They are evidence that my survival strategy as a very frequent flyer often works: if your plans get screwed up, look for a new opportunity or at least a fresh story. Real writers know that if nothing goes wrong you don't have much of a story. However, as I embarked on nearly 20 hours of straight travel from my home to Prague on Monday, I decided I could do without a new story on this trip. I announced as much to the airline gods: "I don't need a new story today."

They heard me, up to a point. All my flights arrived on time, or early, connections were easy, and my bag came to meet me as I walked to the carousal at Vaclav Havel airport. On the longest flight, from Dulles to Vienna, the only empty seat on the plane was the one next to mine. So I got extra legroom and sprawl space, but no interesting conversation with a stranger. There was the small matter of the baby three rows ahead of me. This was the loudest howling baby in human history. Every time it started up, it felt like an air raid siren had gone off just above my head. This happened every fifteen minutes, without preamble, for the whole 8-hour flight. Goodbye to any chance of sleep or proper rest on that redeye flight, though I had boarded sleep-deprived afetr staying up reading most of the previous night. However, the howler in the night brought me an unlikely gift. As I was ripped again and again out of drifty liminal states, I found that I had strong imagery and compelling ideas for a possible new book I had never considered before, though if I bring it off it will marry many of my life themes, dream adventures and experiences of walking on the mythic edge. I can't say more until the writer in me has had a chance to work on this. Writers write. I have never been inclined to say too much about what may be in the works until the work is done. But I'll share my one liner from the trip: A howler can monkey with you to a purpose.

Drawing by RM.

Monday, September 21, 2015

In the dream fitting room, clues to parallel lives

It's happened again. There I was last night, strolling down Jermyn Street in London in a very smart double-breasted gray suit. I haven't worn clothes like these in decades. I haven't put on a tie since my daughter's wedding years ago, and my idea of dress-up is chinos with black sneakers. Yet in the dream, I am my present age, leading the life I might have lived if I had never moved to upstate New York, never started dreaming in the Mohawk language, never become a dream teacher - and remained a bestselling novelist.

The other Robert's life ain't shabby. He has grown as a writer, specializing in literate spy novels set in the darkest years of the mid-20th century, somewhat akin to Alan Furst. He is a time traveler with a special agenda, using active imagination, along with good research, to enter the lives of people in the era of Hitler and Stalin.

I have no wish to swap lives with him, but I'm glad to see he is thriving in his own way. If ever I feel a twinge of regret for a path not taken, I can console myself with the knowledge that in another reality the path was taken.

I've long been fascinated by dream experiences of parallel lives. These can take many forms. We find ourselves in the situation of a person living in a different time. We seem to be enjoying - or not enjoying - a continuous life in another reality. We slip into the perspective and apparently the bodies of other people (including even members of other species) who may be living in our present world, but are not ourselves.

The other Robert's life ain't shabby. He has grown as a writer, specializing in literate spy novels set in the darkest years of the mid-20th century, somewhat akin to Alan Furst. He is a time traveler with a special agenda, using active imagination, along with good research, to enter the lives of people in the era of Hitler and Stalin.

I have no wish to swap lives with him, but I'm glad to see he is thriving in his own way. If ever I feel a twinge of regret for a path not taken, I can console myself with the knowledge that in another reality the path was taken.

I've long been fascinated by dream experiences of parallel lives. These can take many forms. We find ourselves in the situation of a person living in a different time. We seem to be enjoying - or not enjoying - a continuous life in another reality. We slip into the perspective and apparently the bodies of other people (including even members of other species) who may be living in our present world, but are not ourselves.

The parallel life experiences that intrigue

me most are those in which we seem to find ourselves traveling - in an

alternate reality - along paths we abandoned in this lifetime, because of

choices we made. Contemporary science speculates about the existence of

(possibly infinite) parallel universes. In our dreams, we have the ability to

gain experiential knowledge of this fascinating field.

In dreams like the one of the fancy suit, I quite frequently

find myself living in a city or a country where I used to live, doing the

things I might well be doing had I stayed in a former line of work and a

certain life situation. In these dreams, I am my current age, but my life has

followed a different track from the one I have taken in my waking reality. There is

a "just-so" feeling about these dreams. I return from them thinking,

"Well, that's how things might be if I had made a different choice."

Sometimes I'm quite relieved that I made the choices I did; sometimes I feel a

little tristesse for something or someone left on the "ghost trail"

I've seen in my dream ; but most often my feelings are entirely non-judgmental.

This theme is nicely explored in a novel

titled The Post-Birthday World, by Lionel Shriver. Through

alternating chapters, we follow alternate event tracks in the life of the

heroine, depending on whether she did or did not kiss a man other than her

partner on the night of his birthday. That night, her world split. We follow

her double life, through those alternating chapters, and the dual narrative is

beautifully wrought. At the end of the twin tellings, it's hard to make a value

judgment between the alternate life paths. You can't really say that one is

better or worse than the other; they are simply different.

Through a chance encounter that was the

product of a missed airline connection, I once met a woman who told me she was

living a double life of this kind every night (or every day, depending on your

perspective). Every night, she went home to her husband at their comfortable

house on an island off the North Carolina coast. They might go to their

favorite restaurant, or to the mall or the country club. In the morning, they

went off on their separate ways to work. The shocker was this. The man she went

to every night in her dreams was a different husband, in a different house in a

different island. "Whenever I close my eyes," as she told it,

"I'm in a different world. It's the same as this world, but everything is

different."

Under the Many Worlds hypothesis now widely entertained by physicists, it's possible that every choice we make results in the creation of two or more new universes.

Under the Many Worlds hypothesis now widely entertained by physicists, it's possible that every choice we make results in the creation of two or more new universes.

In Parallel Universes theoretical

physicist Michio Kaku suggests that another universe may be floating just a

millimeter away on a "brane" (membrane) parallel to our own. He

explains that we can't see inside it because it exists in hyperspace, beyond

the four dimensions of our everyday reality. But in fact, we can and do go there

- in dreaming and in the imagination.

Synchronistic encounters and moments of déjà vu can help to awaken us to the reality of parallel worlds, as explained in my book Sidewalk Oracles. Imaginative fiction helps open our minds to what is possible. In Borges' 1941

novella "The Garden of Forking Paths" a sinologist discovers a

manuscript by a Chinese writer where the same tale is recounted in several

ways, often contradictory. Time is conceived here as a "garden of forking

paths", where things happen in parallel in infinitely branching ways.

Borges conveys how all possible outcomes of a given event may take place simultaneously,

each one opening a new array of possibilities.

It's fascinating to speculate on what may

happen if parallel selves, and their parallel worlds, bump up against each

other. Could we combine the gifts of different life experiences, or would we

compete with each other? One approach to this theme is a creaky old Roger Moore

movie titled "The Man Who Haunted Himself", hilarious to watch now

because of its silly, jingly circa-1970 musical score. An arrogant, power-mad,

womanizing s.o.b. finds enlightenment, and becomes softer and kinder to the

point where his family, his office and his girlfriend can't figure him out.

When his other self - the s.o.b. in the Savile Row pinstripes - turns up,

everyone accepts him as the true Roger Moore character, and Mr. Softer and

Kinder is shut out of his home and his office.

Leading-edge physicists recently renamed the Many Worlds hypothesis. They now talk of Many Interactive Worlds, exerting mutual influence that usually escapes human perception. As I walk the streets that parallel Robert is walking, is it possible that our lives begin to converge? Is he dreaming more? Am I more drawn to the period and the themes that fascinate him, and to his genre?

I take a sideways look at that smartly dressed fellow in London, through the window my dream opened. He's decided to buy a new dress shirt, and is stepping into Turnbull & Asser, no less, with this intention. Price tags are immaterial to him. I'll leave him to it, as I pack old jeans and polo shirts for my trip today, to places in Europe he also visits, on his own track. However, I pop Night Soldiers, a beautifully written spy novel by Alan Furst, set in eastern Europe in 1934, into my carry-on bag.

Sunday, September 20, 2015

Dreaming yourself in a different body

Have you dreamed of being in the situation and seemingly the body of another person?

Maybe you looked in a mirror and saw a quite different face. Maybe, as you left the dream, you noticed you were wearing clothes of the opposite sex (and are not a cross-dresser). Maybe you weren't aware that you were not your regular self until you tried to figure out the who, what, when, where of what was going on in the dream.

Experiencing things with the perspective and senses of another person is a common experience for psychic dreamers, which frequently requires them to pause and ask: who am I in this dream? This kind of transference is especially common, by my observation, among women who are closely related, as mother-and-daughter, sisters, intimate friends, They wake with information that may be disturbing or delightful, and then have to check on whether the details are actually from another's person's life and imminent future.

In dreams, we enter parallel lives in which we are traveling roads abandoned or not taken on our current event tracks. We also enter the lives and apparently the bodies of characters who are quite different from our present selves. In this way, we learn about our family of personalities connected across time and place within the multidimensional self. We gain insight into past life dramas - whether they belong to an ancestor or a previous incarnation of our spirit - that are relevant to our present life choices.

Of course, dreams in which we inhabit different identities reveal different aspects of our personalities, including the ones Jung called the shadow and the anima or animus. Yet the experiences can also be transpersonal.

Such "body-hopping" experiences can also expand our humanity. They open the locks between different kinds of people and different levels of society. As a mere man, I am grateful for dream adventures in which I find myself in a woman's body. As a white man from a fairly privileged background, I am grateful for dream experiences that take me inside the life situations of people of different ethnicity in far less privileged circumstances. As an Anglo whose three countries of residence - Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States - have not been invaded or occupied in recent generations, I am grateful for dream episodes in which I am in the situation of a person seeking to survive under conditions of war and occupation.

I am smiling now as I remember one of my most entertaining, and increasingly relevant, nights of body-hopping dreams.

More than 20 years ago, I found myself, in a dream sequence that became lucid, in a series of unfamiliar bodies. In the first episode, I am in the body of a black basketball player. I enjoy the things he can do with his magnificent athletic body, and his very active sex life. Then, as an unpleasant scene involving racial bigotry is starting to develop, an inner voice warns, "Get out before you succumb to his rage."

I blink my eyes. In the next instant, I am in a very different body. It belongs to a prosperous middle-aged white guy in plaid pants who is playing golf with his buddies at a Midwestern country club, The scene makes me think of Dan Quayle. It is heaven to the golfer, hell to me. I scream inwardly, Get me out of here!

Now, in the climactic scene, I am in the body and situation of an eccentric, independent scholar of a certain age. He is free to purchase any book he likes and add it to his three-floor home library. He is weaving mental connections between different cultures and practices beyond what anyone has done before. He is highly respected by those who read him and attend his classes, but he remains very human, even humble.

I like his life. I don't like the pains he feels in his legs. What happened to his right knee? What is that occasional stabbing pain in his left heel?

Still, I'll take his life over the others, any day.

Twenty years later - seven years since I injured my right knee, a year since bursitis in my left heel was diagnosed - I recognize I am in the body of that eccentric scholar. It does not take higher math to count the three floors of the home library that is now mine. When you find yourself in another body in a dream, don't dismiss the chance that it is a body that you will some day occupy.

Photo: Locks by Wanda Burch

Thursday, September 10, 2015

Follow Your Own Merlin

Merlin has a thousand

faces. He is magician, enchanter, poet, trickster, prophet, wise or scheming

adviser to kings, the hero or anti-hero of countless dramas and several TV

series. In the Four Ancient Books of Wales,

his name is Myrddin, but in later texts an L was substituted for the Ds – it is

said – because in the ears of the Anglo-Norman nobles who read Geoffrey of

Monmouth’s version in the 12th century, the old form sounded too close to the

French merde. In Geoffrey’s Vita Merlini (c.1150)

“ He was a king and a prophet, to the proud people of the South Welsh he

gave laws, and to the chieftains he prophesied the future.” He is Welsh, he is

Briton, he is Scots, he is universal.

Merlin is a dreamer,

though in some of the ages in which he was remembered this was no term of

praise. In Thomas Malory’s Morte Darthur, his enemies denounce him

as “a wytche and dreme-reder”. In Shakespeare’s King Henry IV,

Hotspur sneers at Welsh boasts about “the dreamer Merlin and his prophecies”

and “such a deal of skimble-skamble stuff.” Merlin’s company is that

of the awenyddion, or “inspired ones”, of whom Gerald of Wales

wrote that “their gifts are usually conferred upon them in dreams.”

Merlin is a shaman,

perhaps the very model of the Celtic shaman. I was greatly helped, back in

1985, by Nikolai Tolstoy’s book The Quest for Merlin, in which

he tracks the shamanic Merlin’s phosphorescent footsteps not only through the

literature but through the landscapes of the Scottish Borders, all the way to

Hart Fell (“Deer Mountain”) where one of the Merlins ran wild with the deer,

conversed with a tame wolf and a little pig, and shamanized by a chalybeate

spring where the waters bubbled rust-red. This Dumfriesshire landscape is that

of my paternal ancestors. Many years ago – using Tosltoy as my Baedecker –

I walked from the site of a ruinous battle whose expense of blood and kin drove

this Merlin temporarily mad to Hart Fell, the mountain of his dreaming

As

the legends and landscapes stream together in my mind, I see the Merlin I know

and love as shaman – which is to say, arch-dreamer – in the following essential

ways:

-

he is born different from others (some say the spawn of an incubus, some of a

golden one) yet cares for and helps and counsels those in need

-

his calling is renewed by a spiritual emergency (his distress over a terrible

battle and then the noise of the world)

-

he is at home with the trees (he finds sanctuary inside an ancient apple tree,

and feeds on apples and nuts, and shamanizes among oaks and hazels and birches)

-

he knows the animals and can take their forms (he rides from his wooded

mountain on the back of a stag, surrounded by a herd of deer)

-

he knows the gates and paths of the Otherworld and can guide others along them

(in one telling, he makes a narrow bridge between this world and an island on

the Other Side)

-

he sees the future, and can bring accurate knowledge of what is to come that is

valued by others (a primary function of true shamans, as far back as we can

know or imagine)

-

he is master of story, poetry and song, through which bardic arts he can

redefine and so remake the world around him

-

through his own wounds, he finds the power to heal the wounds of others (he

loses his mind, but regains it when his shining double, Taliesin, reminds him

of the courses of heaven and earth in poetic speech, and so opens a magical

spring – so Merlin can then offer the same waters of healing to another, to

help him bring his spirit back into the body).

We

are drawn to him by his company, of warring kings and lustful queens and

questing knights. Yet Merlin, for me, rises beyond Arthur and Guinevere and

Lancelot and the company of the Round Table, and even Morgan le Fay, though I

dream of them too, and felt close to the knightly band when I stopped in

Carlisle en route to the Scottish Borders.

We

dream of Merlin, and it may be he brings dreams to us. My Merlin, lover of

woods and deer and poetic speech, is not confined to the ”glass house”

where a lovely female apprentice is said to have confined him after she tricked

him out of his master spells.

My

Merlin travels with a magic orchard that goes with him everywhere. If you are

very lucky, he may offer you an apple, either silver or gold. When you bite

down, you’ll taste not only the sweet juice of the apple, but the heady power

of a story – a story that will inspire you and give juice to your life –

slipping into you. The dream shaman who gives us the right stories is the

Merlin I follow.

Adapted from Dreaming the Soul Back Home by Robert Moss. Published by New World Library.

Art: Druid in Raven Cloak by Robert Moss

Tuesday, September 8, 2015

Yeats practices symbol sending in Sligo

I have returned to my studies of W.B.Yeats, the poet, magus and maker of mythologies.

I was intrigued to notice that as a youth in Sligo, Yeats had early practice in what was then called "thought transference" in games he played with his mother's brother George Pollexfen. Uncle George, who often appeared crabby and distant to others, was a visionary and a spirit-seer. Man and boy would walk by the water, one on the shore and another on the bluff, beaming "symbols" to each other and then checking the results. WBY noted in his Autobiographies that when two people shared a symbol, a dream “would divide itself between them, each half being the complement of the other.”

George Pollexfen later joined WBY in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and they engaged in astral journeying or "mutual visioning" together intended to build a Celtic Castle of the Heroes on the inner planes. For several years, Yeats followed a plan to establish an order of Celtic magicians at a wildly romantic site, the ruined castle on Lough Key, the "Lake of Cé", a legendary druid devoted to the god Nuada.

I describe a personal experience of "tuning in" to a mutual visioning session between Yeats and his friend Florence Farr in The Boy Who Died and Came Back. Mary Greer gives a vivid account of magical work of this kind by Yeats and his intimate circle in her excellent book Women of the Golden Dawn.

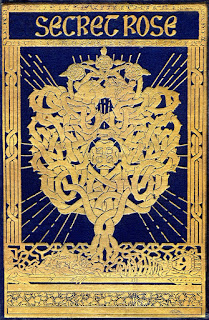

The very latest new Yeats books on my reading table are Talking to the Gods by Susan Johnston Graf, an intriguing study of the role of Golden Dawn practices in the lives and writing of WBY and three other writers (Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood and Dion Fortune) and a beautiful subscriber-funded edition of Yeats' early story collection The Secret Rose, bound together with a novel of WBY's early life by Irish writer Orna Ross. I am proud to be listed among the subscribers who helped to bring this to publication.

In any line of research, the question arises: how far can you go without becoming entangled in a jungle of material indefinitely? The Yeats material continues to sprout, Jumanji-like. The literary scholarship devoted to WBY is probably exceeded (in English) only by that given the Bible and Shakespeare. There are now industrious literary detectives analyzing which pages were dog-eared in books from WBY's library, and tracking the metallurgy and samurai traditions associated with "Sato's ancient blade", a 500-year-old sword presented to Yeats by a Japanese admirer which became a recurring symbol in his work, including the important and disturbing late poem "A Dialogue of Self and Soul".

I gain, always, by returning to the poetry, which I read in the much-used early Macmillan edition of the Collected Poems that I received when I was awarded the Ellis Prize for Verse at my high school graduation. I find that Yeats' poems grow, not diminish, in power, with growing knowledge of how they came to be. Though I have long held that a poem must be its own explanation, I also know the truth of WBY's declaration: "A poet writes always out of his personal life, in his finest work out of its tragedy, whatever it be, remorse, lost love, or mere loneliness; he never speaks directly as to someone at the breakfast table, there is always a phantasmagoria." So it seems right to inspect the personal life as the seed bed and the mythico-magical studies and practice as feed for the flowering phantasmagoria.

There is knowing through books, and then there are other ways of knowing. When I was working on the book that was published as The Dreamer's Book of the Dead, WBY turned up in my inner sight and declaimed, "What better guide to the Other Side than a poet?" I have written quite openly about how "my" Yeats proceeded to grow my understanding of transitions after death, including what happens to discarded subtle bodies in the astral realm of Luna, and how those who have died visit survivors in the phase he called "Dreaming Back" in an effort to get their life stories straight.

Yeats took me, in a lucid dream journey, to a magical environment on "the fourth level of the astral plane"; you can read about that here. In a series of dreams and visions, he also introduced me to special places in Ireland, especially Sligo, that were part of his magical geography. Some of these I have yet to visit, and this is high on my list for future travel.

Image: The ruined castle on an island in Lough Key, where Yeats hoped to base a Celtic magical order, the Castle of the Heroes.

Friday, September 4, 2015

The dream key to Awen

Awen - inspiration -

was, as Caitlin Matthews reminds us, "the supreme preoccupation of Celtic

poets, especially among those who had inherited the ancient prophetic and

visionary arts of the ovate or faith - probably the earliest form of Celtic

shaman." [1]

The word awen derives from the Indo-European root -uel, meaning 'to blow', and is kissing cousin with the Welsh, awel meaning "breeze". In contemporary druidism, awen is depicted as three rays emanating from three points of light.

The word awen derives from the Indo-European root -uel, meaning 'to blow', and is kissing cousin with the Welsh, awel meaning "breeze". In contemporary druidism, awen is depicted as three rays emanating from three points of light.

We have a precious

twelfth-century account of the importance of dreaming in the access to awen for the ancient Celtic poets and

prophets. The source is Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis) in hisItinerary of

Wales. Gerald describes the

practice of the awenyddion, or

"inspired ones". In a key passage, he writes:

Their

gifts are usually conferred upon them in dreams, Some seem to have sweet milk

or honey poured on their lips; to others [it seems] that a written document is

applied to their mouths, and immediately on rising up from sleep, after

completing their chant, they publicly declare that they have received this

gift. [2]

Notes:

1. Caitlin Matthews,

"The Three Cauldrons of Inspiration" in Caitlin and John

Matthews, The Encyclopaedia of Celtic Wisdom. Shaftesbury, Dorset and Rockport MA: Element,

1994, p. 219.

2. Translation from

Gerald of Wales in Nikolai Tolstoy, The Quest for Merlin. : Little, Brown, 1985, p. 140.

Art: "The Bard" by John Martin (1817)

Labels:

awen,

awenyddion,

bard,

Celtic dreaming,

Celtic inspiration,

druidism,

druids,

Giraldus Cambrensis

Hoofprints of the Goddess

Horses run through our

dreams. We wake, hearts pounding, still feeling the thunder of the hoofbeats.

Our dream horses are not the same, of

course. Some are oppressed by dreams of a black horse that seems like a figure

of death, or a red horse foreboding war and bloodshed, or a ghostly pale horse

that brings the sense of sorrow and bereavement. Such dreams - and Fuseli's

famous painting of nightmare - have encouraged the belief that the

"nightmare" has to do with a mare, whereas in fact (the etymologists

tell me) the "mare" part here is most likely derived from the Old

Germanic mer, meaning something that crushes and oppresses.

In dreams, the state of a horse is often a

rather exact analog for the state of our bodies and our vital energy. When you

dream of a starving horse, you want to ask: what part of myself needs to be

nourished and fed? You dream of horses flayed and hung up under the roof beams

(as did a dreamer in one of my workshops) and you need to ask: which parts of

me have been flayed and violated in the course of my life, and how do I heal

and bring those parts back to life?

Such a dream also evokes the ancient

rituals of horse sacrifice - common to many cultures - and might also require a

search back across time into primal material from the realm of the ancestors,

lost to ordinary consciousness, but alive in the deeps of the collective

memory. In the opening of the Brihadaranya

Upanishad, the whole universe is likened to a sacrificial horse.

In Greek mythology, horses are the gift

of Poseidon, and come surging from the sea, their streaming manes visible in

the whitecaps. Or they irrupt from the dark Underworld, from whence Hades

charges on his black stallions to ravish Persephone with his unstoppable sexual

energy and hurl her into a realm of savage initiation beneath the one she

knows. Yet in Arcadia, Persephone's mother Demeter, the great goddess of Earth

and grain and beer, was depicted with a horse's head.

Go to the British Isles, and you find the white mare revered as the mount and form of the Goddess. Her prints still mark the land whichever way you ride, even if only by train or car or Shanks' pony. In ancient Ireland, a true king was required to mate with the white mare, as the living symbol of the sacred Earth. (It would take a manful king indeed to couple with a mare; I suspect a priestess was substituted.) In Wales, she is Rhiannon, and she comes mounted on a white horse out of Annwn, the Underworld, to marry a prince.

In Gaul and throughout the Roman Empire, she is Epona, a name related to the Gaulish epos, “horse”. She is usually depicted riding side-saddle on a mare or between twin horses. She was hugely popular in Gaul and the Rhineland, but was also known in Britain. She was regarded as a patron by cavalrymen. The Aedui, used as auxiliaries by Julius Caesar, prayed to her to protect their horses (and themselves) in battle. To the wider community, she was a Mother Goddess, and her imagery often suggests fertility. On a stone relief of Epona at Brazey in Burgundy, a foal is beneath the mare she is riding, possibly suckling. She often appears carrying baskets of fruit or loaves of bread. She was awarded her own official festival in the Roman calendar, on December 18.

Miranda Green comments, in her excellent book Animals in Celtic Life and Myth, “The horse is absolutely crucial to Epona’s definition: the equine symbolism gave rose to many different levels of meaning, with the result that Epona was worshipped not only as patroness of horses but also as a giver of life, health, fertility and plenty, and as a protectress of humans even beyond the grave.”

Epona was associated with death and rebirth beyond the grave. She is often depicted in Gaulish cemeteries. At a burial ground of the Medioatrici near Metz, images of Epona were offered by relatives of the deceased; one depicts the goddess on her mare, leading a mortal to the Otherworld.

We know the horse in living myths as healer and teacher, as vehicle for travel to higher realms, and as the source of creative inspiration. It is the hooves of Pegasus, rending the rock, that open the Hippocrene spring, beside the grove of the Muses, from which poets have drunk ever since. It is Chiron the centaur, the man-horse, who is the mentor of Asklepios, the man-god synonymous with healing, especially through dreams. In fairy tales (the Grimms' and others) it is often the horse that can find the way when humans are lost.

Go to the British Isles, and you find the white mare revered as the mount and form of the Goddess. Her prints still mark the land whichever way you ride, even if only by train or car or Shanks' pony. In ancient Ireland, a true king was required to mate with the white mare, as the living symbol of the sacred Earth. (It would take a manful king indeed to couple with a mare; I suspect a priestess was substituted.) In Wales, she is Rhiannon, and she comes mounted on a white horse out of Annwn, the Underworld, to marry a prince.

In Gaul and throughout the Roman Empire, she is Epona, a name related to the Gaulish epos, “horse”. She is usually depicted riding side-saddle on a mare or between twin horses. She was hugely popular in Gaul and the Rhineland, but was also known in Britain. She was regarded as a patron by cavalrymen. The Aedui, used as auxiliaries by Julius Caesar, prayed to her to protect their horses (and themselves) in battle. To the wider community, she was a Mother Goddess, and her imagery often suggests fertility. On a stone relief of Epona at Brazey in Burgundy, a foal is beneath the mare she is riding, possibly suckling. She often appears carrying baskets of fruit or loaves of bread. She was awarded her own official festival in the Roman calendar, on December 18.

Miranda Green comments, in her excellent book Animals in Celtic Life and Myth, “The horse is absolutely crucial to Epona’s definition: the equine symbolism gave rose to many different levels of meaning, with the result that Epona was worshipped not only as patroness of horses but also as a giver of life, health, fertility and plenty, and as a protectress of humans even beyond the grave.”

Epona was associated with death and rebirth beyond the grave. She is often depicted in Gaulish cemeteries. At a burial ground of the Medioatrici near Metz, images of Epona were offered by relatives of the deceased; one depicts the goddess on her mare, leading a mortal to the Otherworld.

We know the horse in living myths as healer and teacher, as vehicle for travel to higher realms, and as the source of creative inspiration. It is the hooves of Pegasus, rending the rock, that open the Hippocrene spring, beside the grove of the Muses, from which poets have drunk ever since. It is Chiron the centaur, the man-horse, who is the mentor of Asklepios, the man-god synonymous with healing, especially through dreams. In fairy tales (the Grimms' and others) it is often the horse that can find the way when humans are lost.

I dreamed the other night of rounding up a

great herd of wild horses, and understood, waking in excitement and delight,

that this was about bringing vital energy back where it belongs and helping to

shape a model of understanding and practice of soul recovery for communities as

well as individuals, The wild horse racing through our dreams may be the

windhorse of spirit, or vital essence, that needs both to run free and to be

harnessed to a life path and a human purpose.

Of all the shaman terms I have heard,

"windhorse" is my favorite. It is native to at least three traditions

of Central Asia, where the word "shaman" and the shaman's frame drum

(often made with horse hide and commonly called the shaman's "horse")

originate. In Buryat (Mongolian) the word for "windhorse" is khiitori; in

Old Turkic it is Rüzgar Tayi; in Tibetan it is rlung

ta (pronounced lung ta).

When you think about it, the horse is

unlike any other animal. Stronger than man, it yet allows itself to be gentled

and bridled and provided the main form of locomotion for all those centuries

before the invention of the internal combustion engine. As in Plato's image of

the charioteer of the soul, challenged to manage the rival energies of a horse that

wants to go down on a rampage, wild and sexy and possibly

violent, and the steady horse whose instinct is always to go up, to

rise higher, we are challenged by our dream horses to recognize, release and

temper the horse power within us.

In some of my workshops, I lead people on a journey to find their spirit horses and ride them to a very special place where they can reclaim vital soul energy and identity, from a child self who went missing when the world seemed too cruel, or a younger self who separated because of a wrenching life choice. Sometimes these journeys of soul healing result in the beautiful transformation I call spiritual enthronement, when we are able to receive and embody a part of the greater self – sometimes the Goddess self – because we are now ready to live a greater life.

In some of my workshops, I lead people on a journey to find their spirit horses and ride them to a very special place where they can reclaim vital soul energy and identity, from a child self who went missing when the world seemed too cruel, or a younger self who separated because of a wrenching life choice. Sometimes these journeys of soul healing result in the beautiful transformation I call spiritual enthronement, when we are able to receive and embody a part of the greater self – sometimes the Goddess self – because we are now ready to live a greater life.

Follow the hoofprints

of your dream horse and you may find you are on the trail of the Goddess.

Images: (1) Dun horse of Lascaux, cave art from at least 17,000 years ago. (2) Statue of Epona with grain basket and twin horses from Köngen, Germany c. 200 CE..

Labels:

Buryat,

Chiron,

Epona,

horse,

horse dreams,

Pegasus,

Rhiannon,

Soul Recovery,

spirit horse,

windhorse

Wednesday, September 2, 2015

When the dream monkey has got your back

Dreams are individual and sometimes social experiences that

often seem to reflect universal themes. This is part of the fascination of

sharing dreams. We recognize something of our shared humanity as we listen to

someone else's dream, and yet the final decision on the nature and meaning of a

dream experience will rest on working with what is quite specific and possibly

unique to the dreamer.

We need also to be alert to the role of culture patterns in dreaming. Active dreamers come to recognize their personal styles of dreaming and construct personal dictionaries of symbols by keeping and studying their dream journals over time. The monkey in your dream is not the same as the monkey in my dream.

However, if both of us were raised in a traditional Arab family, or a medieval European one, we might have been schooled to think that monkeys in dreams represent criminal or sinful behavior - in ourselves or others - and dream accordingly. If we have been raised in Hindu families in India, on the other hand, we might be primed to dream of monkeys very differently. Indian children are exposed from childhood to popular tellings of the Ramayana in Bollywood films and television series, in comic books, in school plays and from sidewalk storytellers. This might well leave a shared impression that monkey dreams are auspicious. Why? Because in the perennially popular epic the Ramayana the monkey god Hanuman helps Rama to destroy the demon king of Lanka. He later records the whole epic, writing with his nails.

In western India pilgrims are sometimes inspired by monkey dreams to journey to the temple of Balaji (a form of Hanuman) near Bharatpur in Rajasthan. Sudhir Kakar reported that "the dreams typically involved a personal summons from the divine healer, either through the god speaking directly in the dream or through the dream image of one or more monkeys - the symbol of Hanuman. Thus even before they embarked on the healing journey, some patients had begun to send themselves images of reassurance from the unconscious depths, increasing their hope and confidence in the success of the healing mission." *

Kakar's statement that the dreamers" send themselves' messages is obviously couched in the language of Western psychoanalysis. Dreamers who take the road to Balaji see their dreams as a field of interaction with transpersonal powers, and come to the temple, above all, for release from malignant spirits they believe to be the source of physical and mental illness.

These spirits are collectively known as bhuta-preta and are thought to reside in a halfway house between the realms of the living and that of the ancestral spirits (pitri-lok) when not attached to living people. The most troublesome among them are the "ghosts of unsatisfied desires."

From an Indian perspective, it would be good to know that the monkey god has got your back. But "ghosts of unsatisfied desires" could surely give you the sense of monkeys on your back!

There is a marvelous twist on the monkey theme in Vikram Chandra’s novel, Red Earth and Pouring Rain. The Indian novelist's protagonist is a writer named Sanjay. His time on earth is up, but because he is a marvelous storyteller he is able to strike a bargain with Death, who loves stories. So long as Sanjay is able to hold the attention of his audience — who soon fill the courtyard outside his room — he is allowed to live.

As he weaves his tales, Death ceases to be an adversary. Sanjay makes stories for the joy of making stories, and when he is done, he rests his head in Yama’s lap, peacefully accepting his transition to another life. Sanjay the storyteller is a white-faced monkey who is typing his memories of his human incarnations, to be read aloud by children. No writer with a sense of humor will find it hard to identify with Sanjay’s plight and no one can miss the positive valuation of monkeys in the collective dreaming of India.

We need also to be alert to the role of culture patterns in dreaming. Active dreamers come to recognize their personal styles of dreaming and construct personal dictionaries of symbols by keeping and studying their dream journals over time. The monkey in your dream is not the same as the monkey in my dream.

However, if both of us were raised in a traditional Arab family, or a medieval European one, we might have been schooled to think that monkeys in dreams represent criminal or sinful behavior - in ourselves or others - and dream accordingly. If we have been raised in Hindu families in India, on the other hand, we might be primed to dream of monkeys very differently. Indian children are exposed from childhood to popular tellings of the Ramayana in Bollywood films and television series, in comic books, in school plays and from sidewalk storytellers. This might well leave a shared impression that monkey dreams are auspicious. Why? Because in the perennially popular epic the Ramayana the monkey god Hanuman helps Rama to destroy the demon king of Lanka. He later records the whole epic, writing with his nails.

In western India pilgrims are sometimes inspired by monkey dreams to journey to the temple of Balaji (a form of Hanuman) near Bharatpur in Rajasthan. Sudhir Kakar reported that "the dreams typically involved a personal summons from the divine healer, either through the god speaking directly in the dream or through the dream image of one or more monkeys - the symbol of Hanuman. Thus even before they embarked on the healing journey, some patients had begun to send themselves images of reassurance from the unconscious depths, increasing their hope and confidence in the success of the healing mission." *

Kakar's statement that the dreamers" send themselves' messages is obviously couched in the language of Western psychoanalysis. Dreamers who take the road to Balaji see their dreams as a field of interaction with transpersonal powers, and come to the temple, above all, for release from malignant spirits they believe to be the source of physical and mental illness.

These spirits are collectively known as bhuta-preta and are thought to reside in a halfway house between the realms of the living and that of the ancestral spirits (pitri-lok) when not attached to living people. The most troublesome among them are the "ghosts of unsatisfied desires."

From an Indian perspective, it would be good to know that the monkey god has got your back. But "ghosts of unsatisfied desires" could surely give you the sense of monkeys on your back!

There is a marvelous twist on the monkey theme in Vikram Chandra’s novel, Red Earth and Pouring Rain. The Indian novelist's protagonist is a writer named Sanjay. His time on earth is up, but because he is a marvelous storyteller he is able to strike a bargain with Death, who loves stories. So long as Sanjay is able to hold the attention of his audience — who soon fill the courtyard outside his room — he is allowed to live.

As he weaves his tales, Death ceases to be an adversary. Sanjay makes stories for the joy of making stories, and when he is done, he rests his head in Yama’s lap, peacefully accepting his transition to another life. Sanjay the storyteller is a white-faced monkey who is typing his memories of his human incarnations, to be read aloud by children. No writer with a sense of humor will find it hard to identify with Sanjay’s plight and no one can miss the positive valuation of monkeys in the collective dreaming of India.

* Sudhir Kakar, Shamans, Mystics and Doctors: A

Psychological Inquiry into India and its Healing Traditions (Boston: Beacon

Press, 1982) 82-83.

Image:Lord Hanuman recites the Ramayana. Watercolor

on cloth.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)