I have returned to my studies of W.B.Yeats, the poet, magus and maker of mythologies.

I was intrigued to notice that as a youth in Sligo, Yeats had early practice in what was then called "thought transference" in games he played with his mother's brother George Pollexfen. Uncle George, who often appeared crabby and distant to others, was a visionary and a spirit-seer. Man and boy would walk by the water, one on the shore and another on the bluff, beaming "symbols" to each other and then checking the results. WBY noted in his Autobiographies that when two people shared a symbol, a dream “would divide itself between them, each half being the complement of the other.”

George Pollexfen later joined WBY in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and they engaged in astral journeying or "mutual visioning" together intended to build a Celtic Castle of the Heroes on the inner planes. For several years, Yeats followed a plan to establish an order of Celtic magicians at a wildly romantic site, the ruined castle on Lough Key, the "Lake of Cé", a legendary druid devoted to the god Nuada.

I describe a personal experience of "tuning in" to a mutual visioning session between Yeats and his friend Florence Farr in The Boy Who Died and Came Back. Mary Greer gives a vivid account of magical work of this kind by Yeats and his intimate circle in her excellent book Women of the Golden Dawn.

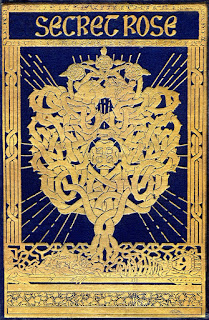

The very latest new Yeats books on my reading table are Talking to the Gods by Susan Johnston Graf, an intriguing study of the role of Golden Dawn practices in the lives and writing of WBY and three other writers (Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood and Dion Fortune) and a beautiful subscriber-funded edition of Yeats' early story collection The Secret Rose, bound together with a novel of WBY's early life by Irish writer Orna Ross. I am proud to be listed among the subscribers who helped to bring this to publication.

In any line of research, the question arises: how far can you go without becoming entangled in a jungle of material indefinitely? The Yeats material continues to sprout, Jumanji-like. The literary scholarship devoted to WBY is probably exceeded (in English) only by that given the Bible and Shakespeare. There are now industrious literary detectives analyzing which pages were dog-eared in books from WBY's library, and tracking the metallurgy and samurai traditions associated with "Sato's ancient blade", a 500-year-old sword presented to Yeats by a Japanese admirer which became a recurring symbol in his work, including the important and disturbing late poem "A Dialogue of Self and Soul".

I gain, always, by returning to the poetry, which I read in the much-used early Macmillan edition of the Collected Poems that I received when I was awarded the Ellis Prize for Verse at my high school graduation. I find that Yeats' poems grow, not diminish, in power, with growing knowledge of how they came to be. Though I have long held that a poem must be its own explanation, I also know the truth of WBY's declaration: "A poet writes always out of his personal life, in his finest work out of its tragedy, whatever it be, remorse, lost love, or mere loneliness; he never speaks directly as to someone at the breakfast table, there is always a phantasmagoria." So it seems right to inspect the personal life as the seed bed and the mythico-magical studies and practice as feed for the flowering phantasmagoria.

There is knowing through books, and then there are other ways of knowing. When I was working on the book that was published as The Dreamer's Book of the Dead, WBY turned up in my inner sight and declaimed, "What better guide to the Other Side than a poet?" I have written quite openly about how "my" Yeats proceeded to grow my understanding of transitions after death, including what happens to discarded subtle bodies in the astral realm of Luna, and how those who have died visit survivors in the phase he called "Dreaming Back" in an effort to get their life stories straight.

Yeats took me, in a lucid dream journey, to a magical environment on "the fourth level of the astral plane"; you can read about that here. In a series of dreams and visions, he also introduced me to special places in Ireland, especially Sligo, that were part of his magical geography. Some of these I have yet to visit, and this is high on my list for future travel.

Image: The ruined castle on an island in Lough Key, where Yeats hoped to base a Celtic magical order, the Castle of the Heroes.

No comments:

Post a Comment