There is a fascinating ambivalence about dreams and dreaming in Buddhist tradition. On the one hand, Buddhism begins with a conception dream of the Buddha’s mother, Queen Maya, in which a numinous white elephant enters her body and is then born through her. On the other hand, ordinary dreams are often dismissed as the product of confusion and the work of the “three poisons” of desire, hatred and fear.

The dreamworld

is a realm of illusion – but so is everything in the experience of a human who

has not attained spiritual liberation. The great Tibetan lama Milarepa counsels

his disciples that dreams are of no importance – and then instructs them to pay

close attention to their dreams and tell them to him in the morning; his favorite

pupil, Gambopa, brings a powerful prophetic dream that previews the spread of

Buddhism in

In

In an excellent and

very readable scholarly study, Angela Sumegi explores the creative tension

between Tibetan Buddhism and shamanic dreaming. In Dreamworlds of Shamanism and Tibetan Buddhism, Sumegi demonstrates

how, while retaining its philosophy of transcendence, Buddhism in

I interviewed Angela Sumegi on my “Way of the Dreamer” radio show in 2010, when her book came out. There was a little

magic in play that day. I rose on the

morning of the interview with two fragments from the hypnopompic zone, the

intermediate state between sleep and full waking. In a vivid dream scene, I

watched Central Asian riders gallop across a great plain where everything was

verdant green. Above them, thunderheads came rolling across the sky. When I

looked at the lightning, I suddenly saw it as the riders did – as a fiery god,

resplendent in red garments, hurling thunderbolts as he rode the sky on a great

charger.

When the scene

receded, a word came into my mind with quiet insistence: Kalachakra.

I thought these

scraps from my dreamlife might be a rehearsal for my interview. Prior to

recording the radio show, I took Angela’s book along to a conference at a

medical center, where I was kept waiting for much longer than expected. This

gave me a chance to re-read sections of her book, including a discussion of the

concept of tendrel to which I’ll turn

in a moment. The person who cleared the logjam at the doctors’ office was a

very efficient and pleasant Jamaican. His origin interested me, because I had

noticed that Angela Sumegi was born in

This seemed like

a meaningful coincidence. It also felt auspicious, in relation to the

interview, since the first Jamaican had played such a helpful role. Might this

be an example of the workings of what Tibetan Buddhists call tendrel?

I put the question to Angela Sumegi on the air. She reminded me that the word tendrel is a contraction of a longer phrase referring to the Buddhist doctrine of “dependent origination”, according to which all phenomena arise “dependent on causes and conditions”. It is also used to mean “sign” or “omen”. So the word applies both to the practice of reading signs in coincidence, natural phenomena, divination kits and dreams - and to a deep philosophy of hidden causes. Tibetan paintings show the twelvefold manifestation of the principle of dependent origination around the Wheel of Life: old age and death arise from birth, etc., etc. As Sumegi explains in her book: “The principle that all phenomena arise interconnectedly and interdependently applies without exception to every existent, linking them throughout time and space; what appears to be a random or chance occurrence can be analyzed in terms of its connections.”

We agreed that my Jamaican sequence might be an example of tendrel at work in the divinatory sense of an omen that felt promising. It also hinted at hidden patterns of causation and connection.

We were already deep into the practice of dreaming. In dreaming cultures, dreams are not isolated from “signs” in the way of Western dream analysis. You read signs in dreams; you also look for dreamlike symbols in the midst of everyday life.

I told Angela the fragments from my dreams and asked her what the Tibetan mind would make of these. She went to the right place (from my point of view) immediately, by telling me that Tibetans would want to know my feelings around the dreams. I am firmly convinced that the first thing we need to know about a dream is how the dreamer felt about it, on first waking. My feelings around the dream scene of the horseman on the verdant plain were of excitement and driving energy, which Angela proceeded to confirm in commenting on the positive energy she felt in the horses and the lush green of the landscape.

What about that word, Kalachakra?

“It’s the great Wheel of Time,” Angela explained, “and the most complex and profound of the approaches to Tantra. It is also the name of a ritual His Holiness the Dalai Lama conducts frequently.”

As we discussed the Kalachakra ceremony, we noticed that it features dreaming. Monks hand out sheaves of kusha grass – long blades to place under the mattress, shorter ones to tuck under the pillow. Grass to dream on, and to invoke only good dream experiences.

Angela suggested that the way the word “Kalachakra” had come to me might be an example of what Tibetan Buddhists call a dream of “permission”: an invitation to proceed to a deeper connection with a practice or a deity.

By now, I was enjoying our

conversation hugely. I knew already the depth of Angela’s research, including

the years she has spent in

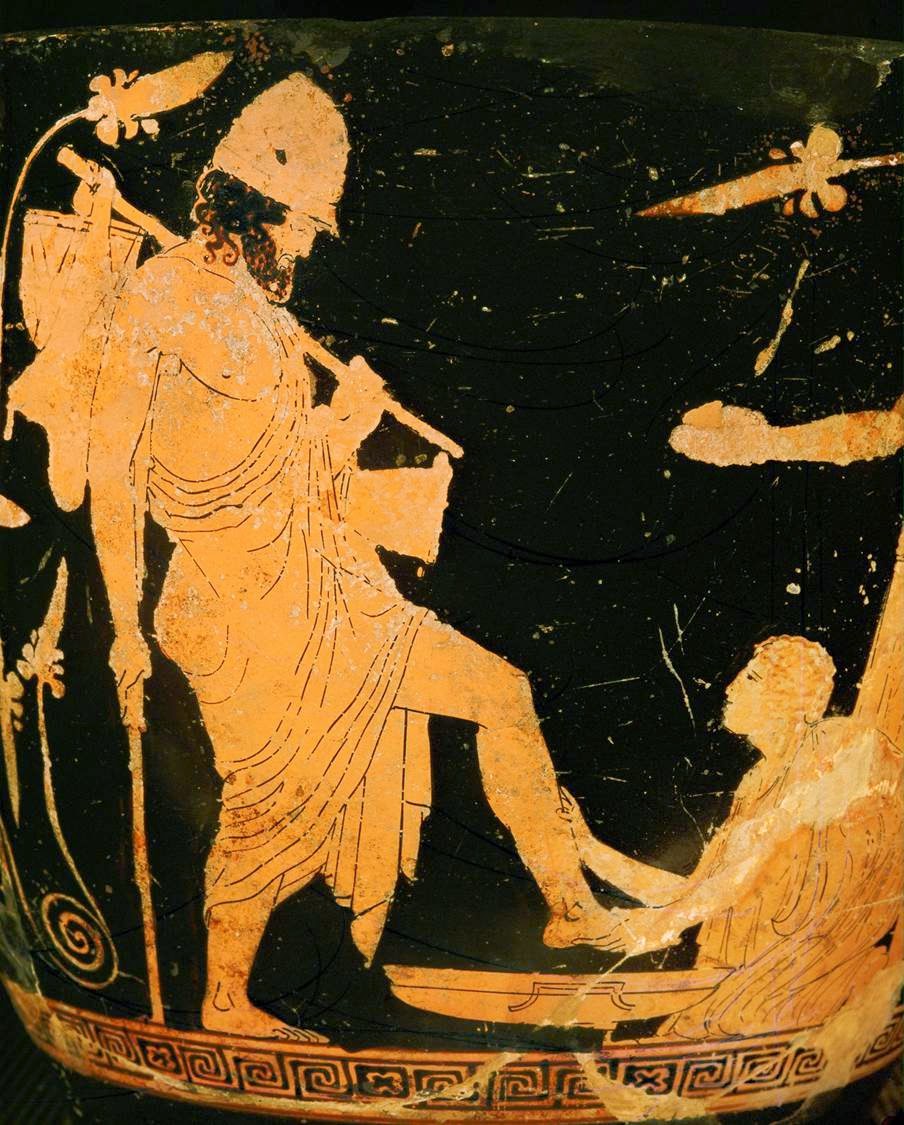

Picture: 12th century Tibetan Mahakala in Rubin Museum of Art