Mircea Eliade is best known in English as a historian of religion, but he was also a prolific author of fiction and fantasy. He regarded the long novel published in English as The Forbidden Forest as his chef d'oeuvre, but many readers will find its loops and repetitions wearisome. However, his shorter fiction can be captivating while evoking some of Eliade's favorite philosophic themes: how the sacred is "camouflaged" in the profane, how at any turning we may encounter a moment of theophany, when the divine irrupts into everyday life and we are released from limits of time and space.

I have been rereading the stories published in translation as Two Strange Tales. Perhaps we should call stories like this nonfiction fantasy rather than fiction. In "Nights in Serampore", Eliade makes himself a lead character. He assigns roles to actual people under their real names, in this case well-known people he encountered in India: the Russian (Eastern Orthodox) scholar of Islam Bogdanov,

the Dutch Secretary of the Asia Society, van Manen, and Swami Sivananda

(“Shivananda” in this version). The two Westerners, with the narrator (Eliade

himself) are in the habit of driving to a rich man’s house in the woods near

Serampore, sixteen miles from Calcutta, for long nights of talking, smoking and

drinking in a lovely setting, in the perfumed air.

A mystery develops. A Hindu professor

reputed to be a master of tantra and yogic siddhis is seen on the road in his

dhoti with the saffron stripes on his forehead. Questioned later, he denies having been there. He

is spotted again, after Eliade has been discoursing on “awful” methods used to

acquire occult powers in Hindu tradition, like meditating all night while

seated on a corpse. That evening, as the threesome leave the rich man’s house,

something strange happens during the car ride. It is taking far longer than it

should to get to the highway, the trees are getting bigger and bigger. Eliade

closes his eyes for a moment and when he opens them the jungle is wild and

unfamiliar.

They hear a woman’s screams. They

get out of the car and follow a flickering light through the jungle. It brings

them to charcoal burners, and an old, rather grand house. The owner receives them,

but moves and speaks very slowly, using only an archaic form of Bengali.

The visitors are confused. They forget the screams that brought them here. Then they remember something, and start to ask questions. The owner of the house informs them that they heard the screams of his wife as she was stabbed to death. Look, here is her body, being carried in on a bier.

Eliade and his friends leave in discomfort and confusion. They can hardly stay when the lady of the house has just been murdered. Weary and drained, they pause under a tree where Eliade takes a nap. Eventually they find their way back to the car. The driver acts as though they never left. Confounded, Eliade and his companions retrace their steps. They return to the tree where Eliade took a nap. They see their footprints on the

ground and follow them. They come to a clearing where the signs of their passage end. There is no grand house, no charcoal burners, no murdered woman being prepared for cremation.

They learn that there was a great house at this place, but that was a hundred and fifty years ago, before it was burned to the ground. The case of the murdered woman, whose name was Lila, was notorious. She died resisting men who were trying to abduct her. It seems

that Eliade and his friends were transported across time. Their adventure was not only metaphysical, since it produced

physical effects – their torn and dirtied clothes, their footprints on the ground.

When they seek to make sense of this, their suspicions fall on Suren

Bose, the yogi magician. Could he have worked an enchantment, to distract them

from spying on whatever he was doing in the forest? How could this be?

Eliade’s question remains unanswered

until he goes to a monastery in the Himalayas and tells his story to Swami

Sivananda. The swami explains: “No event in our world is real, my friend. Everything that exists in this universe is illusory. Not only the death of Lila and

her husband’s grief, but also the encounter between you, living men, and their

shades – all these things are illusory. And in a world of appearances, in which

no thing and no event has any permanence, any reality of its own – whoever is

master of certain forces can do anything he wishes. Obviously he doesn’t create

anything real either, but only a play of appearances.”

When Eliade struggles with this,

Sivananda stages a demonstration. The swami squeezes Eliade's arm and drags him along. Eliade

staggers. Hi senses blur. Now he seems to be in a different time and place, back in the humid forest of the

south. Sivananda makes him walk faster. He is again at the charcoal kilns, at

the big house in the forest. “Wake me up!” Eliade pleads.

In his introduction to Two Strange Tales, Eliade discusses the importance

of fiction in his work. Both stories turn on the use of supposed yogic

techniques to wield occult powers. The mélange of reality and fiction in these

stories, he observes, is well-suited to his concept of “camouflage”, of how the

sacred is concealed in the profane. He writes that

in these two stories

“camouflage” is used in a paradoxical manner, for the reader has no means to

know whether the “reality” is hidden in “fiction” or the other way round,

because both processes are intermingled.

A favorite technique of mine aims

at the imperceptible yet gradual transmutation of a commonplace setting into a

new “world’, without however losing its proper, everyday or “natural” structure

and qualities...The parallel world of the fantastic

is indistinguishable from the given ordinary world, but once this other world

is discovered by the various characters it blurs, changes, transforms or

dislocates their lives in different ways.

Each tale creates its own proper

universe, and the creation of such imaginary universes through literary means

can be compared with mythical processes...The imaginary universes brought to

light in littérature fantastique disclose some elements of

reality that are inaccessible to other intellectual approaches.

The second story, "The

Secret of Dr. Honigberger", involves another real person, a colorful German-Romanian from Brasov. The narrator (Eliade himself) receives an invitation

from a Mrs Zerlendi to inspect her husband’s Oriental collection. He

arrives at the kind of house that often features in Eliade’s fantastic tales,

“one of those houses that I never can pass without pausing for a closer look”,

an old villa behind an ironwork fence and an overgrown garden with a

dried-up pool, where a world disappearing from other parts of the city is

strangely preserved. The main entrance is protected by a sunroof of frosted glass, of the kind that

struck me when I visited Eliade’s old neighborhood in Bucharest, on a street near

Mantuleasa.

Eliade is seduced by an immense library of 30,000 books. We

learn that Mr. Zerlendi was doing research for a biography of Honigberger, a German-Romanian from Brasov who became famous for his adventures in the East.

However, Zerlendi disappeared many years before. Going through Zerlendi’s

notebook, Eliade finds clues to what happened. Among all his composition books, Zerlendi left a journal written in Sanskrit, correctly assuming that it would take a rarely qualified investigator to recognize and interpret its contents. In this journal he recorded his experiments with yogic techniques, including the art

of invisibility.

Central to his practice was the kind of dream yoga or lucid dreaming that places high value of maintaining continuity of consciousness between waking, dreaming and other

states.

After some time I woke up sleeping, or, more precisely, I

woke up in sleep, without ever having fallen asleep in the true sense of the

word. My body and all my senses sunk into deeper and deeper sleep, but my mind

didn’t interrupt its activity for a single instant...

I was astounded to behold, with my

eyelids closed, the very same scene as I had with my eyes open…I saw in any

direction I wanted to, I saw wherever I turned my thoughts, whether or not I

had my eyes open.

He sees others moving in their dream bodies.

The unification of consciousness is

attained by means of a continuous

transition, that is, one without a hiatus of any sort, from the waking state to

the state of dreaming sleep, then to that of dreamless sleep, and finally to

the cataleptic state.

Eliade comments: “All the Indian ascetics that I have known

who have consented to give me any explanations regarded this stage, the

unification of the states of consciousness, as the most important of all.

Anyone who did not succeed in experiencing this could never derive any

spiritual benefit from following yoga practice.”

Dr Zerlendi applied himself to placing himself in cataleptic

trance for longer and longer periods. He believed he had proved that he stepped

outside time when he rose after 36 hours to find his face as freshly shaven as

when he lay down. He laid in suspended animation for 12 hours without

drawing breath. He declared, in his secret book, “I know the way to Shambhala. I know how to get

there.”

He made it his aim to transport himself to Shambhala. To do

this he would have to step outside time. He practiced the art of invisibility as a step towards gaining the power of teleportation, de-materializing in one reality in order to re-materialize in another.

Seized with excitement, Eliade smuggles the journal out of the house, in order to study Zerlendi's techniques closely. He will return the book covertly before anyone notices it is missing.

There is a slight problem. When Eliade returns to the house to interview Mrs Zerlendi again. When he

succeeds, nobody remembers him. He protests that he was working in the library for two full months. This is quite impossible, they tell him. There is no library in the house. There used to be one, but it was broken up and sold off twenty years before.

Eliade goes to the house again, hoping that it will be as he first found it. Now the whole scene is falling apart, like a broken dream. The Zerlendi house is being pulled down.

My favorite passage in the story: "I have always divided people into two categories: those who understand death as an end to life and the body, and those who conceive it as the beginning of a new, spiritual existence. And I never form an opinion of any man I meet until I have learned his honest belief about death."

Nonfiction fantasy. I like the genre description I just invented. In Eliade's case, it not only means that he gives himself permission to use the identities and circumstances of "real" people, starting with himself. It means that the stories are derived from experiences in realities beyond the physical that may be no less real and sometimes intersect - magically or catastrophically -with the world of the senses.

Quotations are from Two Strange Tales by Mircea Eliade, published (appropriately) by Shambhala (Boston, 1986). The translation is credited to Herder & Herder.

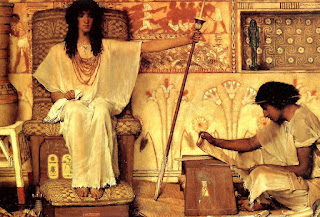

Art: "Nights in Serampore" by Christian Bode (2016)

.jpg)