We did preparatory work seeking protection for the journey, clarifying the intention, and developing personal portals. Most people present had dreamed of dead relatives, and such dreams are often the ideal gateways. Going to the graveyard would of course be a classic Romanian entry point; a typical dream shared in the group began “I was in the graveyard again.” I offered a generic scenario for the crossing by water, adding a mist that would clear to reveal a new landscape on the other side.

The Black Dog came to guide me while I drummed for the group.

I found myself traveling upwards,

through many levels separated by what might have been translucent glass. Up

above, on the sixth or seventh level, was a man who had arranged his

body in some kind of lotus posture.

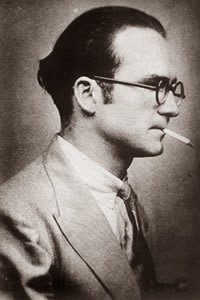

He was wearing an Eastern garment, but I knew at once that this was Mircea Eliade, the great Romanian writer and scholar of religions. He had been dead since 1986, but that was no obstacle to conversation, since I had also left my body, in part of my consciousness.

“What are you doing like that?” I asked him.

He signaled mentally that he had taken up the correct posture for an Avalokiteshvara. I

He was wearing an Eastern garment, but I knew at once that this was Mircea Eliade, the great Romanian writer and scholar of religions. He had been dead since 1986, but that was no obstacle to conversation, since I had also left my body, in part of my consciousness.

“What are you doing like that?” I asked him.

He signaled mentally that he had taken up the correct posture for an Avalokiteshvara. I

“Oh, come on,” I said to Eliade. “Come down from there. I want to talk to you.”

He obliged, taking on the semblance of a professor with glasses in a fairly good suit with a vest. He told me that the biggest regret of his life was that he had failed to become a bestselling novelist. That was his great ambition. Becoming a world scholar of religion was his second choice.

“But look at all you gave to the world.”

He still nursed that regret. He counseled me not to miss my own opportunity to write new fiction that will seize a wide audience, drawing on my travels between the worlds. He urged me to read all of his fiction, and his journals from the time when he was writing fiction. I should re-read “The Gypsies” and feel free to borrow from its plot and techniques. I allowed that I might do this, but only when safely off the road, at home.

Next day, I led our Romanians into the Magic Library. I wanted to

resume my conversation with Mircea, so I transported myself to the used

bookstore just off a busy square in Bucharest where I found an anthology

containing his story “The Gypsies” in October 2012. The place seemed even dustier

and moldier than before, the noise of traffic and construction outside even

louder, and I sensed Mircea insisting that if I wanted a meet, I must choose a

more salubrious setting.

I thought of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, where he was professor of religion. I was instantly transported to a room of Mesopotamian antiquities. I found myself in front of a marvelous Assyrian statue of a god of water. The carved stone streamed, like water, all down his body.

Mircea appeared in a sport jacket. He now had some very specific research leads for me. He explained the significance and the location of a porphyry column that had featured in one of my dreams overnight. He suggested a book project that excites me; it will involve rewriting an ancient myth. I will not say more about that until I have worked on it.

I thought of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, where he was professor of religion. I was instantly transported to a room of Mesopotamian antiquities. I found myself in front of a marvelous Assyrian statue of a god of water. The carved stone streamed, like water, all down his body.

Mircea appeared in a sport jacket. He now had some very specific research leads for me. He explained the significance and the location of a porphyry column that had featured in one of my dreams overnight. He suggested a book project that excites me; it will involve rewriting an ancient myth. I will not say more about that until I have worked on it.

I researched the Assyrian water god in the Oriental Institute and made

a wonderful discovery. He is a guardian figure from an ancient temple of Nabu,

god of writing and knowledge. He holds a vessel from which four streams

of water flow. Two streams rise over his shoulders to flow down his back, Two

flow down the front of his garment to his feet. A superb image of creative

flow, associated with a god of writing. Yes, this was the right place to

discuss new book projects.

Now I am doing the first part of my assignments: reading and re-reading Eliade, especially the fiction, the memoirs, the journals. In his twenties, full of ideas that were bursting for expression, and a constant need to pay for the next meal or the next consignment of books, he wrote in a frenzy. He wrote from 2 PM to 8 PM, and again from 11 PM to 3 AM or later until his body was exhausted and his creative springs ran dry. In the first volume of his Autobiography, I found this passionate statement of creative will: "Nothing, absolutely nothing, can sterilize spiritual creativity so long as a man is - and realizes himself to be - free. Only the loss of freedom, or of the consciousness of freedom, can sterilize a creative spirit."

Today I re-read "The Gypsies." This story is quite edgy for me. I read it for the first time on a plane from Bucharest to Warsaw a year ago. I found it profoundly disturbing and disorienting. In the story, a man is drawn into a strange house that belongs to gypsy witches. Later, he is unable to find his way back to the time and place he came from. Twelve years have flown by; nobody knows him. They won't take his money on the tram because the currency has changed. When he stumbles back to the house of the gypsy girls, we get the impression that he has crossed into a land of the dead.

With an anthology containing this story in my hand, I embarked from Bucharest airport a year ago full of good cheer. My journey rapidly devolved into craziness and confusion. Stranded overnight at Warsaw's Chopin airport thanks to a canceled connection, I found myself fog-bound in the morning and reached a point of desperation when I wondered whether I would ever be able to find my way home. There are stories that take possession of your reality. I found my way back, significantly, by working with elements from a half-forgotten dream.

In the anthology of Romanian Fantastic Tales translated by Ana Cartianu (Bucharest: Minerva, 1981) that got me into trouble in October 2012, Eliade's story "La Țigănci" is simply titled "Gypsies". In the translation by William Ames Coates reprinted in Tales of the Sacred and Supernatural (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1981) it is given the fuller title "With the Gypsy Girls".

wonderfull ...

ReplyDeleteHow great to meet Mircea Eliade.

ReplyDeleteDidn't know he had been a professor of Religion, but makes perfect sense. His book on Shamanism, is a favorite of mine.

In my dream that I wrote about on a resent post of yours the distant ancestors where concerned that Iwould not find my assignment because I paused to talk with them and let the young man in the black coat go ahead of me to my assigned room. I reassured them that this guide was a magnet for me. I could find him anywhere in the dark. I have a thread of dreams with him. One where he was a gypsy leader and I helped a tiger escape a Catholic Church in an Eastern European country. Another where I tried to hide that I was a magic one because He was so fond of the women and I was too attracted to him. To be a writer for me Is essential to living Free. It keeps the flow in the layers of my self free of constipation. Not such an eloquent statement. I have been secretly in love with writing and reading since I was finally able to read. Also I believe that I did not want to be born during this time. My soul is such a gentle one really. Embracing and learning Inanna again will be an empowering balance for this embodied woman. When I do re membering work, I am always surprised by what I have kept in hiding about myself. And I am always delighted when I find myself walking whole. Consciousness of freedom and the creative spirit are important for me to nurture, within and without. One more thing, I believe the act of taking, wether it is as a raping of Mother Earth, or from pushing one self too hard or not asking nicely or ... Is a rampant dis ease in this time.

ReplyDelete